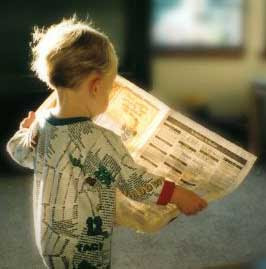

Good readers, we now know, have habits that make them better at reading. They make connections, they visualize, they question and predict, and they make inferences about what they're reading. Today we're going to look at another habit: determining importance.

My 3rd grader recently had to read the opening chapters of Dear Austin, a book about the underground railroad, and pull out 3 important details. She had to do this without really knowing what was going to happen next in the book. In this sense, she was predicting, but in another sense the exercise forced her to examine how the author wrote to try to figure out if any weight was being given to particular details, details which might be central to the story.

My 3rd grader recently had to read the opening chapters of Dear Austin, a book about the underground railroad, and pull out 3 important details. She had to do this without really knowing what was going to happen next in the book. In this sense, she was predicting, but in another sense the exercise forced her to examine how the author wrote to try to figure out if any weight was being given to particular details, details which might be central to the story.In the first few chapters we learn that 1. Levi has been left behind when his family went to Oregon because he was ill. 2. His friend, Jupiter, is the son of former slaves. 3. Levi hates dancing. 4. Levi lives with a guardian, Miss Amelia. 5. Levi is often in trouble for boyish pranks. 6. Jupiter never speaks and that some people say he saw something terrible when he was a baby that scared the voice right out of him. 7. Levi has a friend named Possum. 8. Jupiter has a sister named Darcy who sings all the time.

Now we have to weigh that information. We know quite a bit about Levi and his life, but what qualifies as important? What's going to impact the story later on? Even without having read the book, you can guess from the above list that points 2 and 6 are likely to be important to the rest of the story. Partly we know this because we have wide experience with books --we know how a book is 'set up' and we can guess where it might be taking us. We gather clues from the back cover, from things our teacher or parent says, from the cover picture, and we use that to help filter and rank the details as they come in. Also, we can guess at their importance because the author devotes just a skosh more description to them than to the other pieces of information she gives us. And, those things seem the most likely ones that you could build a story around. We sense that there's a deeper mystery here to Jupiter's silence.

One way to thinkk about this is to consider which details you would include if you had to tell someone about a book. What details of the plot would you include? As soon as you can, even with picture books, get your child to re-tell you the story. This helps them with their ability to pull out the plot of the book. Keep doing this as the books get longer and more complex. Talk about the details of the book and try to figure out which might be most important to the story. Look at the cover, the back cover, the pictures in the book -- in picture books, the most important parts of the story are usually the ones that are illustrated. In a sense, you are determining importance backwards: you read the story and then decide what was critical. BUT, this is fine because it gives kids a picture of how books work, how details contribute to the overall story. Eventually, they'll develop a sense of which details are likely to be important and be able to predict with a fair amount of accuracy.

One way to thinkk about this is to consider which details you would include if you had to tell someone about a book. What details of the plot would you include? As soon as you can, even with picture books, get your child to re-tell you the story. This helps them with their ability to pull out the plot of the book. Keep doing this as the books get longer and more complex. Talk about the details of the book and try to figure out which might be most important to the story. Look at the cover, the back cover, the pictures in the book -- in picture books, the most important parts of the story are usually the ones that are illustrated. In a sense, you are determining importance backwards: you read the story and then decide what was critical. BUT, this is fine because it gives kids a picture of how books work, how details contribute to the overall story. Eventually, they'll develop a sense of which details are likely to be important and be able to predict with a fair amount of accuracy.

Determining importance is easy to do with a good writer. Good authors will often spend more time on important details -- describing a place or person very thoroughly -- if they're going to figure prominently later in the book. They tend to spend less time on minor characters and unimportant details. Also, they'll often repeat things that are important or contribute to the theme.

Learning to determine importance is a process; don't be discouraged if your child doesn't get it right away. My 3rd grader, who is a very proficient reader, was completely stumped by her Dear Austin assignment. But that's okay: it was a teaching moment. And now, when she encounters a similar assignment, she'll have that experience to fall back on.

Next Up: Good Reader's Habit #6: Synthesis

Access to books is a critical aspect of

Access to books is a critical aspect of

A nice addition to the Highlights stable is High Five, their magazine for 2-5 year olds. The text is much simpler, pictures are larger and fill the pages. It has the same focus on good morals, though the message is obviously greatly simplified. One lovely feature of both these magazines is no advertising.

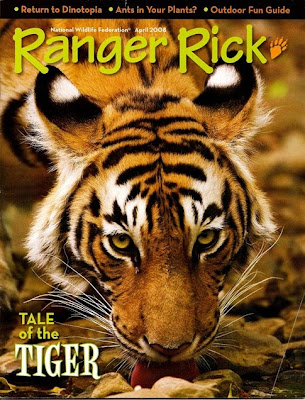

A nice addition to the Highlights stable is High Five, their magazine for 2-5 year olds. The text is much simpler, pictures are larger and fill the pages. It has the same focus on good morals, though the message is obviously greatly simplified. One lovely feature of both these magazines is no advertising. I absolutely love these next three, put out by the National Wildlife Federation: Ranger Rick (at the top of this post) Your Big Backyard, and Wild Animal Baby.

I absolutely love these next three, put out by the National Wildlife Federation: Ranger Rick (at the top of this post) Your Big Backyard, and Wild Animal Baby. One nice feature about Wild Animal Baby is that it comes in a board book format of heavier cardboard, rather than flimsy magazine pages. It's perfect for little hands to hold. The photography in all these magazines is fantastic and the range of articles is impressive -- whatever animals your little ones like, they'll show up eventually in these pages, one way or another. Another blessing: no ads to disrupt your reading.

One nice feature about Wild Animal Baby is that it comes in a board book format of heavier cardboard, rather than flimsy magazine pages. It's perfect for little hands to hold. The photography in all these magazines is fantastic and the range of articles is impressive -- whatever animals your little ones like, they'll show up eventually in these pages, one way or another. Another blessing: no ads to disrupt your reading. National Geographic Kids is another one we get, but I would be lying if I said it was a favorite. It was a gift, otherwise I'd cancel my subscription. I find the layout overly busy and it's loaded with ads for candy and video games. Additionally, it contains feature articles on movies -- special effects, actor interviews, etc. Not strictly National Geographic stuff -- more along the lines of paid endorsements. In and among the plugs are some interesting articles about animal rescues, critter cams, and habitats, but it's pretty buried in junk. Ostensibly for 6-14 year olds, but I can't see kids sticking with it that long.

National Geographic Kids is another one we get, but I would be lying if I said it was a favorite. It was a gift, otherwise I'd cancel my subscription. I find the layout overly busy and it's loaded with ads for candy and video games. Additionally, it contains feature articles on movies -- special effects, actor interviews, etc. Not strictly National Geographic stuff -- more along the lines of paid endorsements. In and among the plugs are some interesting articles about animal rescues, critter cams, and habitats, but it's pretty buried in junk. Ostensibly for 6-14 year olds, but I can't see kids sticking with it that long. Another one for 2-6 year olds that gets good reviews is Ladybug. It's colorful and full of stories, poems. The publishers also have a magazine called Babybug, which is made of heavy stock like Wild Animal Baby. They also publish one called Click! which is geared more towards science and nature.

Another one for 2-6 year olds that gets good reviews is Ladybug. It's colorful and full of stories, poems. The publishers also have a magazine called Babybug, which is made of heavy stock like Wild Animal Baby. They also publish one called Click! which is geared more towards science and nature.

If you have a sports nut, Sports Illustrated for Kids might be a good choice. Parents rated this one very highly because it focuses on the positive achievements of athletes and their good sportsmanship, rather than on their questionable activities and sexual antics. One word of caution here would be that kids may assume the adult version of SI is okay because of their exposure to SIKids. Obviously the articles in SI are going to burst some bubbles, so that's something to consider.

If you have a sports nut, Sports Illustrated for Kids might be a good choice. Parents rated this one very highly because it focuses on the positive achievements of athletes and their good sportsmanship, rather than on their questionable activities and sexual antics. One word of caution here would be that kids may assume the adult version of SI is okay because of their exposure to SIKids. Obviously the articles in SI are going to burst some bubbles, so that's something to consider. Appleseeds is a magazine full of non-fiction and social studies articles for kids ages 7-9. Each issue covers a particular theme: Becoming President, Whiz Kids, Unusual Structures, Halloween. Rather a narrow age range, but the content makes it of use in giving kids experience with non-fiction text.

Appleseeds is a magazine full of non-fiction and social studies articles for kids ages 7-9. Each issue covers a particular theme: Becoming President, Whiz Kids, Unusual Structures, Halloween. Rather a narrow age range, but the content makes it of use in giving kids experience with non-fiction text.

Cricket has been around since the '70s and is another publication that celebrates fiction, though this time from established, even classical writers like Shakespeare, Robert Frost, Shel Silverstein, and Lloyd Alexander. It also includes games and puzzles. It's geared for 9-14 year olds.

Cricket has been around since the '70s and is another publication that celebrates fiction, though this time from established, even classical writers like Shakespeare, Robert Frost, Shel Silverstein, and Lloyd Alexander. It also includes games and puzzles. It's geared for 9-14 year olds.

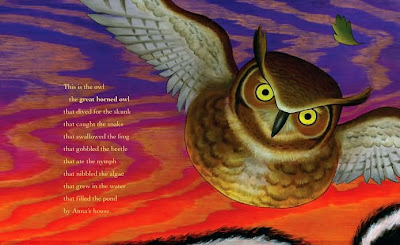

In honor of Earth Day, here's a book for the preschool/kindergarten set that clarifies, very simply and beautifully, the circle of life in a pond. Pond Circle, by Betsy Franco, is written on a "This is the House that Jack Built" model: "This is the algae, the jade green algae," and "This is the skunk, the shy striped skunk," etc. Each animal depends on the others for food, and they all depend, directly or indirectly, on the algae, which is the foundation of the whole pond.

In honor of Earth Day, here's a book for the preschool/kindergarten set that clarifies, very simply and beautifully, the circle of life in a pond. Pond Circle, by Betsy Franco, is written on a "This is the House that Jack Built" model: "This is the algae, the jade green algae," and "This is the skunk, the shy striped skunk," etc. Each animal depends on the others for food, and they all depend, directly or indirectly, on the algae, which is the foundation of the whole pond.

Love the pictures on this one; they're either painted on wood or painted to look like wood grain, the grain itself suggesting the ripples in the pond water or the eddying colors of a sunset. Pictures are all on 2-page spreads, very large and colorful, making this a good choice for a group read-aloud. This one will play especially well with preschoolers because of its engaging rhythm and repeated word patterns.

Love the pictures on this one; they're either painted on wood or painted to look like wood grain, the grain itself suggesting the ripples in the pond water or the eddying colors of a sunset. Pictures are all on 2-page spreads, very large and colorful, making this a good choice for a group read-aloud. This one will play especially well with preschoolers because of its engaging rhythm and repeated word patterns.

Wordless picture books rely almost entirely on making inferences to understand the story. Take

Wordless picture books rely almost entirely on making inferences to understand the story. Take  Here's another scenario, one that's a little more complex in terms of the conclusions that can be drawn. In the book

Here's another scenario, one that's a little more complex in terms of the conclusions that can be drawn. In the book  In picture books, draw your child's attention to the illustrations and ask questions to get at the characters' feelings or motives. In David Gets In Trouble, David tells his mother he wasn't responsible for taking the big bite out of the cake. However, since he's saying it with chocolate crumbs all over his face, get your child to make an inference: do you think he's telling the truth? (no) How can you tell he's lying? (he has crumbs all over him, he has cake on his mouth) Later, David fesses up. Ask: why do you think he told his mom the truth? (he felt bad, he felt guilty, he's sorry he lied, he's afraid she won't love him). Or just model the process for them: "Oh, David has crumbs all over his face -- I think he ate the cake and is telling a lie about it."

In picture books, draw your child's attention to the illustrations and ask questions to get at the characters' feelings or motives. In David Gets In Trouble, David tells his mother he wasn't responsible for taking the big bite out of the cake. However, since he's saying it with chocolate crumbs all over his face, get your child to make an inference: do you think he's telling the truth? (no) How can you tell he's lying? (he has crumbs all over him, he has cake on his mouth) Later, David fesses up. Ask: why do you think he told his mom the truth? (he felt bad, he felt guilty, he's sorry he lied, he's afraid she won't love him). Or just model the process for them: "Oh, David has crumbs all over his face -- I think he ate the cake and is telling a lie about it." With older kids, stop the flow of the narrative and point out the evidence that leads you (and them, watching you) to a certain conclusion. "See, Edmund is trying to make himself seem more grown up, more like the older kids, by selling Lucy out. He's telling them Narnia was all a game -- lying about it -- so he can feel better and bigger than her." In about 3 seconds, you've traced the chain of evidence and drawn some conclusions about it.

With older kids, stop the flow of the narrative and point out the evidence that leads you (and them, watching you) to a certain conclusion. "See, Edmund is trying to make himself seem more grown up, more like the older kids, by selling Lucy out. He's telling them Narnia was all a game -- lying about it -- so he can feel better and bigger than her." In about 3 seconds, you've traced the chain of evidence and drawn some conclusions about it.

Somewhat similar is

Somewhat similar is

It feels weird, at first, to stop the reading and talk through a mental image with your child. But it will feel more natural with a little practice. Don't feel like you have to do it for every facet of every book. Choose events or characters or settings that seem important to the story, or particularly colorful and start there. Or if something strikes you as particularly beautiful, try that. Or pick something that's unclear and work on picturing it together -- that's what good readers do when they aren't quite sure about something they've read; they go back and re-visualize it so they've got it clear in their heads. I think it's particularly helpful to take something unclear to you, the parent, and let your child listen to you talk through your visualizing process. It makes the point that everyone runs into reading snags from time to time, and here's one way to get out of them.

It feels weird, at first, to stop the reading and talk through a mental image with your child. But it will feel more natural with a little practice. Don't feel like you have to do it for every facet of every book. Choose events or characters or settings that seem important to the story, or particularly colorful and start there. Or if something strikes you as particularly beautiful, try that. Or pick something that's unclear and work on picturing it together -- that's what good readers do when they aren't quite sure about something they've read; they go back and re-visualize it so they've got it clear in their heads. I think it's particularly helpful to take something unclear to you, the parent, and let your child listen to you talk through your visualizing process. It makes the point that everyone runs into reading snags from time to time, and here's one way to get out of them.